Over the last few trials, I’ve seen a fair bit of emotion from people just starting out on their trialing journey. This got me thinking about my own transition to this sport, and the adjustment I had to go through in order to be successful (and again, I mean that in relative terms). I thought that this might be the perfect time pass on my thoughts around why I think gundog trailing is a completely different kettle of fish to other dog sports out there. This is not only to offer encouragement to those starting out and finding things hard, but also to help explain why field trials are not like ring sports, and why that’s okay.

As you know, if you’ve read my previous post The Beginning: My Journey Into Gundog Trialing, I was heavily involved in the dog agility world prior to starting out in the gundog scene. While this doesn’t make me an expert, it does give me a unique perspective that many other handlers might not have.

If you’ve come from agility or obedience, gundog work might feel surprisingly unpredictable and hard at first. This doesn’t mean that you or your dog aren’t talented, it just means the skills required are rooted in a different set of traditions with its own rhythm and rewards.

I think it’s helpful to look at these areas of difference to highlight why transitioning from one discipline to the other can feel overwhelming.

So here goes…

The Purpose of Gundog Trails

Gundog work isn’t harder, it’s just different.

The focus, for the most part, is less about precision drills and more about real-world adaptability, control at a distance and natural hunting instincts shaped over time. This is because the discipline of field trials developed out of a genuine need for dogs to perform a job, to be functional, or fit for purpose, in the real world.

Other dog sport disciplines, with the exception of protection work and sheep dog trails, do not have the same vital function. Ring sports do teach and require practical skills, but they are sports that have developed as a pastime for humans to bond with their dog, not as an essential skill required to carry out a essential role. This is important because the level of precision versus functionality differ between the disciplines.

An example of this is when I push for competition level obedience in my peg-work at a trial. In doing so, by overusing verbal to get Hail to perform her heel up or sit at the peg ‘perfectly’, I create unintended pressure. The result of this is that I usually get a random behaviour, such as mismarking, mouthing the bird or dropping it at delivery. Instead, I should be aiming for ‘functional’ obedience at the peg.

Sure, it’s not as pretty as competitive obedience heelwork and definitely wouldn’t stack up to the standard required at an obedience competition, but it’s functional, and that’s all it needs to be for her to perform her role well with a good attitude. I don’t need to teach to the same level of precision here, so why would I?

Where We Train The Skills

One of the biggest differences I noticed when transitioning from agility to field trials was that the skills I was teaching for field trials were hardly ever taught in the same type of environment I would ultimately use them in. Most foundational gundog skills are taught at home, in the living room, in the garden, or (if you’re lucky like me) at the rugby fields with our training class on a Monday night.

None of these environments are even anything close to the environment of a field trial! A field trial is usually on private farmland or somewhere ‘wild’ where there are other dogs, gunshot, wild game, livestock, trial game (usually in the form of dead pigeons), and a whole raft of other distractions including influence from the weather and wind direction.

We cannot expect our dogs to perform with these types of distractions if we haven’t taken the time to teach them first. The only way to have reliability at a field trial is to expose your dog to these types of distractions before the trial. You may even decide to ‘forfeit’ your first few trials and use them as an opportunity to expose your dog to certain distractions if you have no other way to recreate them in training. As my mentor always says, “sometimes you have to spend points to save points”.

This is quite different to sports like agility or obedience where it is easier to recreate ‘competition day’ at training. I’ve been a member of various agility clubs, and I know that weekly training is often set up to mimic the real thing. There is a ring or course set up, with obstacles placed out as they would be in a competition, and an instructor standing on the course acting like a judge. Training in this way prepares the dog for what’s coming, so when your first event rolls round, both handler and dog are a bit more accustomed to what’s about to happen. And there are less external influences outside of your control. In short, you have a lot more control over the environment in ring sports, than you do in field sports.

Unfortunately in gundog training, while you can, and should try to mimic a field trial in your training building up to your first competitions, it is much more difficult to recreate the atmosphere of a trail event on your own. The sport is inherently more unpredictable so it is almost impossible to set up a training scenario that takes into account all the possible distractions and factors that you might experience on the day.

All we can do is our best. So, this might look like finding a few other people to venture out to a ‘wild place’ with to run a few short of drills that include one or two aspects of distraction. But remember, this takes time. This isn’t something you can crash course. It requires a significant time commitment, and miles, in order to gradually expose your dog to as many possibilities as you can without overwhelming them.

Differentiation of the Skill Sets

Speaking from my own experience, I would say that ring sports have the advantage of being able to breakdown or differentiate the skills required between the different grades more easily. The courses can be modified to include, or exclude, certain obstacles or skills to make it easier, or harder, based on the level of the dog.

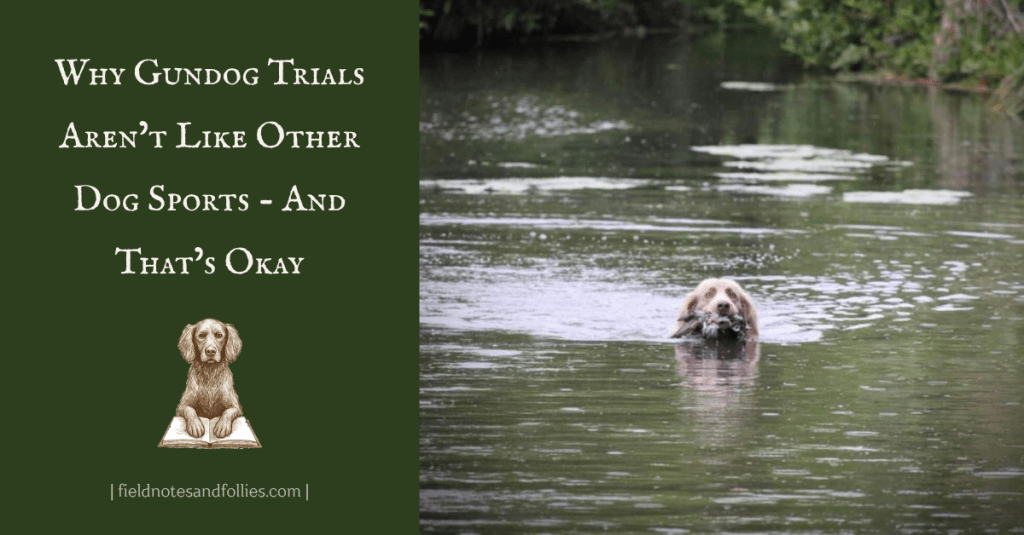

Hail on her water retrieve at the 2024 NZ Weimaraner Club Field Trial.

For example, a Starters or Jumpers C style course in agility has predictable elements (or obstacles) that handlers can expect and these can be taught in a controlled environment. They know what situations can, and cannot, be presented in a competition set up, and they can prepare their young accordingly.

This is why some dogs involved in ring sports can go out and win on their first weekend of competing. Their handlers know the five or six skill sets they need, they know the likely arrangement of how these skill sets can be presented in a course, and they put time into practicing them.

A beginner gundog trial isn’t quite the same. Yes, we know the basic skill sets we need (steadiness, marking, delivery), but as we’ve already discussed, we have no idea what the competition set up will be and we have no idea what distractions or obstacles might be presented to us. This makes it difficult to have an easy mode, or to differentiate the grades, as the nature of field sports require a higher entry point of basic skills in order to complete them. It’s not possible to omit aspects of a trial unless things were done in an unnatural environment.

This is why, while not unheard of in the gundog scene, a win on your first weekend in Novice is exceedingly rare and usually only achieved by very experienced handlers. My advice here is to manage your expectations. Expect that you are going to fumble around in the minor grades for quite some time until you feel you have your bearings. Hail and I have been at this for the best part of three years, and it’s only now that I’m starting to really get a grip on things. That doesn’t mean the last few years were a waste of time. They were all part of the process of learning something new, of truly being a beginner.

The Rate of Progress

Progress in field sports looks and feels much slower. This is usually down to the fact that we are trying to utilise a set of complex skills at distance where we need to harness the dogs natural drives and genetic ability, while also giving the dog enough rope to use their initiative, but not too much that they work completely independently of the handler. Talk about a paradox!

In ring sports, the focus is more on the dog following direct handler instruction, without expecting the dog to make decisions. This is usually with less distance between dog and handler, meaning that the handler has a larger zone of influence over the dogs behaviour during their run.

Running Spel required a lot of direct handler instruction.

The methods used to teach these skills are the same as those used for other disciplines, as teaching is done using positive reinforcement. It’s just that the perceived level of difficulty looks so simple when you watch a good dog retrieve a bird. Additionally, most peoples dog will fetch a tennis ball in the garden, so everyone assumes that fetching game in the field is the same.

What people forget is that in field sports, the dog is retrieving a piece of game, which a potential food item, that they have to happily give back to their handler without a fuss. They have to go through all sorts of unknown cover, obstacles and conditions (that their handler can’t see) in order to get to that game to retrieve it. But before that, they’ve had to sit quietly while a simulated shot has been fired, and they’ve had to watch the arc of the bird as it falls from the thrower. They’ve then had to pinpoint where it landed, and keep that spot in their working memory as they move through the field. Not so simple now, huh?

To work a dog, at distance, without stifling its natural, genetic ability takes time to teach. It also requires experience from both the handler and the dog. Are you getting the sense that field sports are not just a pick it up and put it down kind of hobby?

In Summary… Don’t Lose Hope

To complete even a Novice gundog trial, with single marked birds, requires many layers of skill.

These skills can only be developed over time, with exposure to a variety of situations, that you as a handler, will need to go out of your way to create.

I don’t say this to be discouraging. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. I say this because as handlers we are often quite hard on ourselves, and sometimes our dogs. Learning the skills required to successfully (here, goes that word again) complete a Novice trial are, in my opinion, more challenging that those required to prepare a young dog for an agility or obedience competition. I can almost here the ring sports lynching mob forming as I write this!

So please, don’t beat yourself up if you’re finding it hard. You’re not a terrible trainer, your dog isn’t an idiot. These skills are tough to master, the ‘cost’ of entry is higher and the rate of progress can be uncomfortably slow. I felt all of this when I started out, too.

If you want to succeed, my advice is this. Take every opportunity you get to train your dog in different situations. Create opportunities for yourself, too. Find people to train with. Be open to advice and suggestions from those ahead of you in their journey. Accept that what you’re trying to teach your dog is not ‘basic’. It’s complex, its got to be adaptable, and so do you.

Let me know if this post resonates with you.

If you have any other gems of advice for those struggling with the transition between dog sports, please feel free to share this with them or leave a note in the comments below.

Leave a comment